Low Water Mark

Wednesday, February 1, 2012 at 9:29AM

Wednesday, February 1, 2012 at 9:29AM

Half an hour after work ended, Kei called to say that she was in the neighborhood. I told her to come on up, but she insisted that we meet outside. Whatever. I hung up the phone and clomped down the stairs where I found her at the entrance of my building. She was in a colorful skirt and jean jacket, her soft brown curls resting on denim shoulders. A warm smile appeared on her pretty face.

"It's been a long time, hasn't it," I said.

"Yes, it has," she replied with a quiet, girlish laugh.

We hadn’t seen or mailed each other for almost a month and a half. The last I had heard from Kei was a short mail warning me not to contact her because her husband had become suspicious. And then two days ago she called and told me she wanted to meet.

Kei asked me to take her to a restaurant I had mentioned several months earlier. When we arrived, however, the “restaurant”—no larger than my own living room—was full, so we went to another restaurant two blocks away.

We took a corner table that faced the open doors of a fifth floor balcony, overlooking a desolate parking lot, the quiet Kokutai Avenue, and an ugly mishmash of condominiums and apartment buildings beyond. Not much of a view, but then I had really come to enjoy the scenery outside.

Even before our conversation had begun, I could sense from her nonchalance that what she had written to me in the e-mail had been a lie.

"Your husband never did suspect anything, did he?” I said after our drinks came.

“No.”

"And he's gone now? He's at the dorm studying?"

“Yes.”

Her husband was supposed to be sequestered in a dorm in the countryside to study for a promotion test. When Kei first told me half a year earlier that her husband would be out-of-town for two months, my mind filled with tantalizing possibilities.

“He’s been gone all this time?”

“Yes, but he comes back next week.”

Each confession was like a soft punch. I had been looking forward to her husband’s absence for six months, eager to spend an entire night with Kei for the first time in our three-year-long affair.

I slouched down in my seat, defeated. I never imagined that Kei could be so dishonest to me.

"Don't you think it was a clever idea," she asked.

"What on earth do you mean?"

"I thought for days and days about what to write to you . . ."

"You know, I got that mail while I was still in Thailand. I was having a damn good time until I read it. Ruined my fucking trip, it did. "

"I'm sorry."

"You're sorry," I replied lighting a cigarette.

"Please don't smoke."

Ignoring her, I took a deep, slow drag, let the smoke drift from my mouth to my nostrils.

If only I had had some coke to smoke, instead.

"You're sorry." I told her how much I had worried about her safety, how I had gone by her home to look for signs of life only to find none, and how I hated myself for having been so selfish. "I've always tried to tell you the truth, Kei. Always. Even when I knew that doing so might hurt my chances with you."

The words came out slowly and painfully. My heart clung to each syllable unwilling to let them go, unwilling to let myself admit that this woman I had loved for so long could inflict so much agony.

"I was honest, so that you would understand me and love me for who I was and not for someone you thought I was or someone I wanted you to think I was. I opened myself to you, and in the end you lied. I never thought that you could be so cruel."

I lit a third cigarette. Smoke flowed in a long, twisting trail from my lips.

"When you told me that you had a new girlfriend," Kei began to explain, "I was very jealous. I couldn't sleep for days."

It amazed me how this woman could continue to try to possess me and yet at the same time keep me at a safe distance. It was unnerving at the best of times.

"I'm very possessive," she continued. "I want things only for myself."

I had heard this the previous summer when I told her that I had started seeing a doctor. Suddenly, Kei couldn’t see me enough. We were meeting sometimes twice a week, making love more often than ever before. And it had the desired effect: the doctor soon faded out of my life. But once Kei had me twisted nicely around her finger, she stomped on the breaks.

"You're an only child," I replied. "What do you expect?"

"So, when you told me that you had a new girlfriend I considered trying to make it difficult for you to meet her, to call you up at all times, so that she would end up leaving you . . ."

"That, I have to admit, would have been a hell of a lot better that this."

"I was also angry because you had told me that you weren't interested in other women . . . You know, I was so happy when you told me that last summer."

It was still true. Even when having sex with Ryô, I still thought about and wanted to be with this stupid woman before me now.

"The reason I started seeing Ryô,” I said, “was because the last time you and I made love, you worried so much about getting pregnant that you cut me off. Don't you remember? You said that if you ever did get pregnant, you wouldn't be able to see me again. It was just a matter of timing, is all. I wasn't really searching for someone—I was happy with you, difficult as this arrangement has been—but, someone found me. I was still looking forward to this summer and being able to spend time with you again like we did last summer. I was counting the days until my birthday when the two of us would travel to the countryside together . . . "

"Yes, yes, yes,” she said. “I thought about what to do and decided that lying to you was the best way."

"The best way? You're joking, right?"

"I though that not seeing you for a while would allow you to start a new relationship. I thought it was a good idea at the time, but I'm sorry if you were hurt by it."

The impulse to jump off the balcony to the hard asphalt five floors below clouded my thoughts. But knowing that I'd just end up in a lot of pain rather than dead caused me to slouch deeper in my chair and light another cigarette.

"And there's another thing," she said hesitantly.

"Hmph."

"I'm pregnant."

"How many weeks?"

"Seven. I'm due in January."

Seven weeks. We had had sex only ten or so weeks before. That the child might be mine was met with a tired indifference. I said nothing.

An achingly long half an hour passed in silence as I drank and smoked the last of my cigarettes.

"You haven't looked at me," she said. "You haven't congratulated me either."

"Congratulations," I offered flatly, then left for the restroom.

I stood before the vanity staring at my weary face and wanting to cry for the years of frustration and false hope that I had endured since meeting Kei. But I couldn't; I haven't been able to really cry for years. After regaining my composure, I returned to our table, to my drink, and after twenty minutes of awkward silence asked her if she wanted to go.

She nodded.

We went back to my apartment where I gave her the presents I had bought for her in Thailand.

"Where's the basket?"

"Huh?"

"I asked you to buy me a basket," she said.

"I didn't have the space, and besides there weren't any good ones. Bali's the place for that kind of thing, not Thailand."

"Yes, but you bought all kinds of things for yourself..."

"Of course, I did," I replied, irritation rising. "Christ, you can be incredibly selfish at times."

With this Kei bolted out of my apartment. I chased after her barefoot down the hallway and drag her back as she kicked and slapped me. Once inside, we hugged, tears falling down our cheeks. I looked at her face, her soft almond shaped eyes and kissed her chapped lips. We dropped slowly to the tatami floor and held each other for a while, but I knew this was the end. We were writing the epilogue of a book that had already gone on far too long.

With one final kiss and a long hug, she left.

The next day, Saturday, was a busy day for me. Two lessons in the morning followed by a short break, then four more lessons in the afternoon. Saturday, which had once been my lightest day of work, one I could manage even after a long hard night of partying, was now no different from my other ball-busting workdays: lessons bumper-to-bumper for hours and hours on end. The only difference being that today the drudgery was broken up by a midday tryst with Ryô who came by, fucked me hard, letting me cum the very last drop of my strength in her mouth, then left.

By evening, I was exhausted mentally and physically. But with my first Sunday free of work for the first time in weeks, I wanted to party, to go to some bar and find an easy lay to help alleviate the ache in my bones, but no one was out on the town tonight. Instead, I dug into my bag of tricks, pulled out a small Ziploc bag of psilocybin mushrooms, and watched videos until dawn.

After a few hours of sleep, I woke, then left for a four-hour long exam in Japanese listening comprehension that ended up being much easier, and as a result more disappointing, than I had expected. (Despite nodding off in the middle of the test, I still managed to score in the ninetieth percentile.) Ryô met me in the evening for dinner, after which I tied her up and screwed her for an hour before conking out. When I woke the next morning, I was alone, the ropes I had tied her up with placed neatly at the head of my futon.

The following Tuesday, Ryô and I went to a local amusement park for the day where she ended up blowing me on the Ferris wheel.

If it weren’t for the distraction Ryô was providing me, I don’t know how I’d manage. Kei was right all along: the timing for us to finally part after so many frustrating years couldn’t have been better.

Ryô called me a few days later.

"Why were you born?" she asked.

“Why was I born?”

"Yes, why were you born?" she asked again.

“I, uh, I . . .”

"To love me of course."

And to think I had always thought the reason I was born was to feel the pain of solitude.

“So, I was. So, I was.”

“I love you,” she said.

“Thank you.”

Let it snow

Saturday, January 28, 2012 at 7:05PM

Saturday, January 28, 2012 at 7:05PM

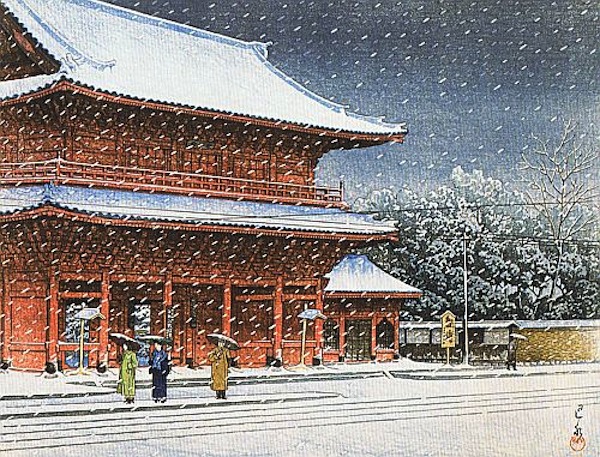

Hasui Kawase's "Zôjôji no Yuki" (1922) It’s been snowing off and on for the past three days here in Fukuoka and the peaks of the mountains to the south and west of the city are now white. It’s tempting to go hiking up one of them. But, then again, who am I kidding?

Hasui Kawase's "Zôjôji no Yuki" (1922) It’s been snowing off and on for the past three days here in Fukuoka and the peaks of the mountains to the south and west of the city are now white. It’s tempting to go hiking up one of them. But, then again, who am I kidding?

On my way to work the other day, I stopped at what the Japanese call a “scramble intersection” (スクランブル交差点, sukuranburu kôsaten), an intersection where pedestrians are allowed to cross every which way they want when the “WALK” sign comes on.

Across the street from me was a salaryman in his late fifties, staring blankly ahead. As we waited for the light to change, fluffy white snowflakes started to fall lazily from the sky.[1] The salaryman’s eyes lifted then followed one of the flakes as it slowly descended, down, down, down, down, and landed softly on the asphalt where it stuck. A gentle smile spread across his face, eyes brightened, and, if I am not mistaken, the salaryman’s day had just been made.

[1] These big snowflakes are called botan yuki (牡丹雪, lit. “peony snow”) in Japanese, which is certainly more poetic and evocative than what we call them in English: “humongous snowflakes”.

These Charming Men

Thursday, January 26, 2012 at 11:26AM

Thursday, January 26, 2012 at 11:26AM

Teaching English in Japan I come across Anglophones from all over the globe who are engaged in the same trade of linguistic orthodontics as me. I also come across a large number of Japanese students who have very fixed, yet often mistaken, notions of national character.

One of the first questions I am often asked by prospective students, particularly those with an intermediate or above level ability in English, is: "Where are you from?"

When I tell them that I am American, most are happy. Some, however, hoping for an Englishman can't quite hide the disappointment in their voices. They ask a number of other questions, but for the most part they have made up their minds and are already looking at the phone number they will dial next.

To these women--it's always women, especially women of good upbrining--your average American may be friendly, but he just doesn't have the cachet of the English. Besides, they don't want to speak American English. Heavens no. They want to speak the Queen's English.

These women will fawn over any man who resembles ever so remotely Hugh Grant. They'll insist on watching only British or European films, too. Four Weddings and a Funeral is one of the perennial favorites. They'll have a fondness for Baroque music and furniture and preference for English tea in European porcelain over a cuppa joe. And on and on.

Funny thing is, I have yet to meet this prototypical Englishman. Most tend to be as rough around the edges as yanks, or, heaven forbid, the Australians, and quite a few have mouths that would embarrass a sailor.

Several years ago, I was listening to a English reporter of African descent talk about his experience covering the United States. One of the things that stayed with me is that in America the British accent adds fifteen or so points to a person's perceived IQ. I think the same can be said here in Japan. Have a English accent and the Japanese will perceive you as more intelligent and cultivated, a more gentle gentleman.

So, it amuses me whenever I come across an Englishman who does or says something that is, for lack of better words, just plain dumb.

Take Nigel (not his real name). Nigel and I play soccer together on a pretty strong team composed entirely of university professors. (I am the second-weakest link on that team, by the way.) Nigel and I often take the train into town together after practice and talk about life.

One of Nigel's recurring topics is how little sex he and his wife have been having. "I suppose I shouldn't really complain: compared to the average Japanese couple," he said in that languid cadence of his, "we do make love more often, but still . . . "

"Oh, with me it's the opposite," I replied, half-jokingly. "My wife is insatiable. You know, sometimes I just want to be . . . held."

"Sometimes, a young girl will come into my classroom, and she'll be so beautiful that . . . " he said with a shy smile. "Here I am forty-one years old and a girl of eighteen makes my heart go pitter-patter."

"It can't be helped," I said. "We're biologically wired to feel that way. Personally, I'm surrounded by young beautiful women because of my work, but I'm so busy and tired all of the time I have no interest in making a move. Of course, if one of them ever deigned to make a move on me, well, I would have no choice but to acquiesce. It is, after all, what Jesus would do."

Changing the subject, Nigel told me he was reading an excellent book and, fishing it out of his duffle bag, showed it to me.

"Ah," I said, taking his copy of Confessions of a Yakuza (浅草博徒一代 Asakusa Bakuto Ichidai) and checking to see how far he'd gotten. "I've read this four times already."

I asked Nigel if he had read any of Junichi Saga's (佐賀純一) other works. He hadn't, so I recommended Saga's first work, Memories of Silk and Straw (田舎の肖像, Inaka no Shôzô) which has a chapter on the gangster whose life story would be retold in Asakusa Bakuto Ichidai and later masterfully rendered into English by John Bester. "Anything translated by Bester," I told Nigel, "is a sure bet."

Talking about the yakuza and novels, Nigel asked me if I had read anything by Mifune.

"Mifune?"

"Yes, Mifune," he replied. "He was a right-wing radical, committed seppuku in the seventies . . . "

"I don't think that's Mifune, you're thinking about . . . "

"No, it's Mifune. I'm certain about that," he said. "Mifune, Mifune, Mifune. What's his first name again. Mifune."

"You know, I don't believe it's Mifune. It's, it's, it's . . . Mi-something. Oh, this is frustrating."

"Yoshio Mifune!" Nigels said triumphantly.

No sooner had we parted ways than the name of the author came to me: Yukio Mishima.

A few days later I was at a friend's Irish bar, The Craic and Porter, when another Englishman came in with a friend and sat down at the table next to mine. Let's call him Graham.

Graham has been in town for nearly as long, if not longer than, as I have. We have seen each other easily a thousand times (nodded to each other several hundred) over the past two decades, but never spoke until that night.

"You play tennis often," I asked. I had seen him playing at the same courts in the ruins of Fukuoka Castle where I myself played once or twice a week.

"I try to get a game in now and then," he answered.

"Me, too. Me, too."

I've been playing tennis for about five years now and am only moderately better than when I started. When I mentioned this Graham contradicted me: "I've watched you play. You're not half bad."

"You're either too kind or have had too much to drink."

Anyways, Graham and his friend went on to chat about this and that, their conversation eventually making its way to music.

"Do you know that Bob Marley song "No Woman, No Cry", he asked his friend.

"Yeah."

"You know what that means?"

You gotta be feckin' kidding me, I thought to myself.

His friend supposed that it had to do with not having a woman in your life and . . .

"No," Graham said, "that's what I used to think, but I was at Allen's place, Xaymaca, the other day and he told me that it meant . . . "

"No, woman, don't cry," I interrupted.

"Yes! That's right!" Graham said, turning to me. "How did you know?"

Good grief. "Well, if you listen to the lyrics . . . "

"Yesh!"

Bob Marley,

Bob Marley,  British accent,

British accent,  Confessions of a Yakuza,

Confessions of a Yakuza,  Craic and Porter Fukuoka,

Craic and Porter Fukuoka,  Englishmen,

Englishmen,  Hugh Grant,

Hugh Grant,  John Bester translator,

John Bester translator,  Junichi Saga,

Junichi Saga,  Queen's English,

Queen's English,  Xaymaca Fukuoka,

Xaymaca Fukuoka,  Yukio Mifune,

Yukio Mifune,  stereotypes in

stereotypes in  Authors,

Authors,  Humor,

Humor,  Japanese Women,

Japanese Women,  Living in Japan,

Living in Japan,  Married Life,

Married Life,  Off Beat,

Off Beat,  Reading Life,

Reading Life,  Soccer,

Soccer,  Teaching Life,

Teaching Life,  Translating Japanese,

Translating Japanese,  Writers

Writers Mieko Kawakami

Wednesday, January 25, 2012 at 9:42AM

Wednesday, January 25, 2012 at 9:42AM

When the disheveled Shinya Tanaka (田中慎弥) plodded onto the stage (see video) to give his interview with the press after winning the prestigious Akutagawa Prize[1] a week ago, I couldn’t help remembering when a very different writer won the prize four years earlier.

When the disheveled Shinya Tanaka (田中慎弥) plodded onto the stage (see video) to give his interview with the press after winning the prestigious Akutagawa Prize[1] a week ago, I couldn’t help remembering when a very different writer won the prize four years earlier.

Mieko Kawakami (川上未映子), a singer and author from Osaka, was awarded the prize in 2008 for her second novel Chichi to Ran (乳と卵, Breasts and Egg).

Mieko Kawakami (川上未映子), a singer and author from Osaka, was awarded the prize in 2008 for her second novel Chichi to Ran (乳と卵, Breasts and Egg).

I have not yet read anything by the author, but if she writes half as good as she looks, forget about Haruki Murakami and short-list this gorgeous woman for the Nobel Prize!

[1] The Akutagawa Prize (芥川賞, Akutagawa Shô) is a semiannual prize given to promising new writers of serious fiction. Established in 1935, it is named after the novelist Ryûnosuke Akutagawa. Mieko Kawakami won the 138th prize; Shinya Tanaka, the 146th.

Pandora's Box

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 11:06AM

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 11:06AM

Reading an old journal entry can be like opening Pandora’s box:

Reading an old journal entry can be like opening Pandora’s box:

Wednesday, 23 May 2000

One of my favorite students, Ikumi, will be moving to Osaka soon. When you're in my line of business you get used to seeing people come and go. Still, with someone like Ikumi, it's not always easy to say good-bye.

I still remember the day she began studying about two and a half years ago. A 28 years old newlywed, Ikumi was so charming that I often fantasized about something developing between us. We definitely had chemistry, but nothing ever happened. Perhaps, if her husband hadn't been the only son of the president of a large company, it might have been a possibility. The man, despite his other charms, is, after all, fat and balding. Ikumi has put on some weight over the years herself, but I still find her as attractive as ever.

Six women came over last night, four of whom, including Ikumi, I wouldn’t mind dating. Unfortunately, only one of them, Eri, is what might be considered "available". At 25, she's been dating the same doctor for years and years and if she's not thinking about getting married anytime soon, is probably open to a liaison. I've always had something of a crush on the cute, narrow-faced woman since she began last summer, but never had the chance to make a move. I may, though, now that Ikumi is leaving and the others have changed classes.

Eri's charm lies in her fresh, natural beauty. Despite working as the receptionist at a cosmetic surgeon’s office of all places, she never wears make up and usually keeps her short, black hair tucked behind her ears. She dresses modestly, too: simple white blouses and jeans.

The other two are Tomoka and Yûka. Both are the nicest of girls. Tomoka, the more beautiful of the two, recently announced that she would finally marry her boyfriend of some seven or eight years. Tomoka, like Eri, is a natural beauty, with a complexion that has never known so much as a zit. She’s so lovely that it has been difficult for me to get excited about the hints that Yûka, her best friend and co-worker, has been giving me for over a year. Yûka is a real sweetheart and rather pretty in her own way but she just can’t compare to Tomoka. I jus know that if I ever did go out with Yûka I would always wish it were Tomoka I was with and that wouldn’t be fair to a girl as nice as Yûka.

I cooked several different dishes—a variety of satay with peanut sauce, a mild yellow curry, a Balinese rice known as nasi uduk, a spicy beef salad called Nua Yang Nam Tok, and three different stir-fry dishes. Three hours of preparation and cooking, and all of it—forgive me for boasting—was pretty damn good.

We sat down to eat at around eight. Having not eaten much recently, my stomach was much too small for the kind of meal I had prepared, so I drank, instead—beer, Bombay Sapphire, Linie Aquavit, Cinzano, Tres Generaciones tequila—enough alcohol to make me worry that I'd be in my own private hell the next morning. (As luck would have it, I would wake early without a hangover—I must have still been drunk.)

Misao was the first to leave, then Eri, Yumi and Ikumi, leaving me alone with Tomoka and Yûka. We had a nice talk about marriage and boyfriends. Tomoka can be surprisingly frank at times. When I asked Yûka whether or not she would get married this year as she had originally planned, she replied that now that Tomo-chan was marrying in July, the pressure was off. One would think the very opposite would be true.

Yûka never seemed too enthusiastic about her own boyfriend. They’d been together for nearly as long, and like Tomo, Yûka had also moved in with her boyfriend. She continued to keep her company dorm, though, out of fear, perhaps, of making the leap. If she does eventually marry the guy, I imagine it will be from inertia more than anything.

Personally, I think Yûka is secretly hoping someone will come along and make it easy for her to leave her boyfriend, and I wouldn't be surprised if it were me that she was waiting for. There was a time and, good Lord, many, many chances when something could have happened, but the window is now closed.

Not long after saying good-bye, the front doorbell rang. Opening the door and expecting to find someone from the dinner party returning to claim, say, a forgotten scarf, I found my lover Ryô, instead, wobbling slightly and her face flush with red.

Having just come from a party with co-workers, Ryô was three sheets to the wind, far drunker than I had ever seen her. "I want you to fuck me,” she said, kicking her shoes off at the entry and stepping into my arms. “I want you inside me."

She removed her own clothes, dropping her dress in the hallway, her stockings in the dining room, her pants and bra in the living room, and for the next hour got what she had come for.

When Ryô was done, she got herself dressed and, telling me she how much she loved me, staggered out my apartment.

Around midnight, I got a call from Canada. It was my wife.

“You drunk?” she asked annoyed.

“No, no,” I replied. “Only half asleep.”

“Well, you sound drunk.”

“I sound like someone who should be asleep in bed and not on the phone.”

We chatted for a few minutes after which she reminded me to not forget to deposit money into her bank account.

“I won’t, I won’t,” I replied irritably. The woman went through cash like a goat through paper.

“Anyways, I was wondering,” she began hesitantly, “if you would mind my staying . . . a full year in Canada.” She had originally planned to stay seven months.

Mind? No, I didn’t mind at all. I wondered, though, if our marriage would survive it.

Putting the Pieces Together

Sunday, January 22, 2012 at 10:44AM

Sunday, January 22, 2012 at 10:44AM

Little Chatterbox This morning, my 20-month old son came into my room where I was sleeping, pointed towards the ceiling and said, "Dark." He then took the remote (this is Japan, everything has a remote) from the table and turned on the light. "On," he said.

He also found my glasses on the table. Picking them up and unfolding the temples, he placed the glasses gingerly on me. This was a first. He then pointed at the clock on the wall and said, "Six!"

I looked at the clock myself and saw that it was seven-thirty. "Close enough, boy."

Eoghan then pointed at my computer and said, "Apple. Nena." He meant that he wanted me to turn the computer on and Skype his grandmother.

It's remarkable how language starts developing, how a child puts the pieces of the linguistic puzzle together and starts communicating.

The Deadly Four

Sunday, January 22, 2012 at 9:51AM

Sunday, January 22, 2012 at 9:51AM

I visited gran'ma in the hospital the other day and confirmed what I had often heard: there aren't any 4s in Japanese hospitals.

Some people may claim that the Japanese are superstitious, pointing out that the number (四, shi) sounds like death (死, shi) in Japanese. Incidentally, the same is true in Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam, countries which like Japan had incorporated this tetraphobia along with the Chinese writing and numerical system well over a millenia ago. No, I think the omission of "four" in hospitals today is influenced more by a desire to avoid upsetting or discomfitting patients than superstitious claptrap.

While I was in Hawaii a few weeks ago, I noticed that our fourteenth floor condominium was actually on the thirteenth floor. When I pointed this out to my wife, a wild-eyed man riding in the elevator with us said it was because the building had been built by Freemasons. It was the first time I'd heard that and have since Googled it to see if there's anything to it. (There is and there isn't.) At any rate, I'm still not convinced. Most likely, the developer didn't want to take any chances that there might be triskaidekaphobes among his future clients. Why make things hard for yourself?

Mind your back

Monday, January 9, 2012 at 10:59AM

Monday, January 9, 2012 at 10:59AM

My back tends to hurt when 1. it's cold, 2. money is tight, and 3. work is busy. On the other hand, my back feels pretty good when 1. it's sunny and hot, 2. money is good, 3. I swim, and 4. I am on vacation.

My back tends to hurt when 1. it's cold, 2. money is tight, and 3. work is busy. On the other hand, my back feels pretty good when 1. it's sunny and hot, 2. money is good, 3. I swim, and 4. I am on vacation.

It's obvious that I need to find a job as lifeguard on some sunny, quiet beach that pays more than six figures, and quick. Wonder if anyone is hiring.

back problems,

back problems,  curing backaches,

curing backaches,  heath in

heath in  Off Beat

Off Beat Of Rice and Men

Wednesday, December 14, 2011 at 4:55PM

Wednesday, December 14, 2011 at 4:55PM

A few months ago, I visited Ukiha Machi in the southern part of Fukuoka Prefecture to see the terraced rice paddies—known as tanada, (棚田) or dandan batake (段々畑)—and the cluster amaryllis (higan bana 彼岸花).

A few months ago, I visited Ukiha Machi in the southern part of Fukuoka Prefecture to see the terraced rice paddies—known as tanada, (棚田) or dandan batake (段々畑)—and the cluster amaryllis (higan bana 彼岸花).

While there I was struck once again by the size of the rice fields: some were as small as a twin-sized mattress, many no larger than a lane in your local public swimming pool. Some were so small I couldn’t help wondering how much rice even the most determined farmer could grow on such a limited space.

And so, curiosity had me going around pestering people to find out just how much rice could be harvested from a field that measured only 1 tsubo.[1] Would there be enough rice for, say, an o-nigiri (rice ball)?

(I asked some of my college students this same question and got answers that varied from 50 rice balls to 500.)

Well, I eventually got around to asking a relative of mine, who like many rural Japanese is a weekend farmer, and was kindly provided with the answer.

Well, I eventually got around to asking a relative of mine, who like many rural Japanese is a weekend farmer, and was kindly provided with the answer.

Rice fields in Japan are measured in tan, which are equivalent to 992m2. Tan atari (反当たり), or tantō (反当), then refers to how much can be harvested from a field. A typical rice field will produce a tan atari of 8 to 9 tawara[2], or 480 to 540 kilograms of rice. Since 1 tan is equal to 300 tsubo, one tsubo would provide 1.6-1.8 kilos of rice. Mind you, this is would be genmai, or unpolished, brown rice. Once polished you would end up with about one shō (一升) of rice, or 1.5 kilograms. Thus, with a-one tsubo rice-paddy you could expect to harvest about one shō of uncooked rice.

1 gō[3], or about 150 grams, of uncooked rice is enough rice to make about two o-nigiri once cooked.

So, that single tsubo patch of planted rice would yield about 20 rice balls. A paddy the size of one tatami mat would give you enough rice for ten rice balls.

[1] The tsubo (坪) is a standard unit of area still used today in Japan to measure land and floor space. One tsubo is equal in size to two tatami mats side by side or 3.31m2 (1.82m x 1.82m).

[2] A tawara (俵) is a straw bag for holding rice. Similar to bushels in the U.S., the tawara is sometimes used to measure capacity.

[3] A gō (合) is another unit used in measuring volume. One gô of uncooked rice contains about 6700 grains of rice.

Makin' Up Don' Have to Be Hard to Do

Thursday, December 8, 2011 at 1:33PM

Thursday, December 8, 2011 at 1:33PM

While many Japanese universities have strict rules about how many lessons must be taught each semester, little is said about the quality and or relevance of those lessons. So, when forced to make up lessons last Saturday for a school day that I will miss due to an up-coming trip, I gave the students a choice between having a regular lesson or the following: going bowling, karaoke, or watching a movie. Had it been summer, I would have also included the popular option of going to the beach which is a short walk away from campus.

It was unanimous: the kids wanted to go bowling.

"The Dude abides."